Some of you may know this already. Late last year I got tenure, and shortly after that I resigned to run a start-up. Given how many people compete for so long to find a permanent academic position, and given how many academics manage to start companies, it might seem like a crazy decision to make. Perhaps it was. However, for me, I think it was the right choice. Let me explain.

I have been obsessed with technology and technological progress since I was a small child. I first learned to code when I was eight, on a Commodore 64 that my dad had bought for my birthday. I was completely obsessed with it, and as I grew older, I thought myself more languages and technologies. I took theoretical physics in university not just because it combined my interests in maths and physics, but also because I could take first year CS along side the maths and physics courses. I thought that if I studied theoretical physics that I would always be able to move into CS, but if I studied CS it would be hard to move into physics later, so I was kind of keeping my options open. I also kind of thought that physicists would be the ones building the most exciting technologies, rather than engineers. For the same reason, I knew that I wanted to get a PhD, because I thought that, frankly, you probably needed a PhD to work on the really cool stuff. These may all be misconceptions, but it was the way I thought at the time. So when it came time to apply for PhDs, the choice of topic was obvious: quantum computing was the one field that seemed to offer the potential to relive the early days of computing.

But that was 15 years ago. So why now? Why spend so long in academia only to leave now?

For much of the time I have been in the field, quantum computing was a bit like nuclear fusion. It seemed certain that it would be possible from the physics, but it seemed to be forever twenty years away, and maybe always would be. But now, at last, it seems like the clock is counting down. What was 20 years away five years ago, now seems to be only 15 years away. I am sure many people will have their own idea of when the turning point came, but for me, I think, it was an IBM talk at the APS March Meeting in 2012. That’s when it felt the clock started ticking for me.

If I had worked on hardware, I probably would have taken the jump to industry or a start-up sooner. IBM and Google are doing fantastically interesting things, and now there is a slew of extremely credible hardware start-ups (Rigetti, IonQ, PsiQuantum, QCI etc.). The Chinese tech giants are also getting in on the game, and it seems like Chinese quantum computing scientists are a hot commodity. If I was part of a big consortium working to build a quantum computer, then perhaps I would not have taken the jump at all. No one has built a useful quantum computer yet, and it may be a long road to that, but that’s what makes it so exciting. I always wanted to work on computers not as they are today, but as they were in the early days, when there was still so much to be done and there were so many opportunities to make a real difference. That’s what makes now special.

There are huge challenges facing the realisation of useful quantum computers, but the challenges are not just on the hardware side. We don’t yet clearly understand where the line is between useful and useless for quantum hardware, and our ability to identify areas of possible quantum advantage and to formulate algorithms for them is still sorely limited. Sure, we know a handful of algorithmic techniques, but when can we apply them? If I ask a software engineer how best to represent a tree on a conventional computer, they won’t hesitate to talk me through the possible data structures. But can we say the same for quantum computing? Where are the data structures? Why is everything a standalone algorithm that is not necessarily composable? If we don’t think about how to do these things now, then we’ll have an even longer path to useful quantum applications. In my view, writing a paper here and there, and jumping on the hot problems that everyone else is working on, isn’t going to get us to where we need to be.

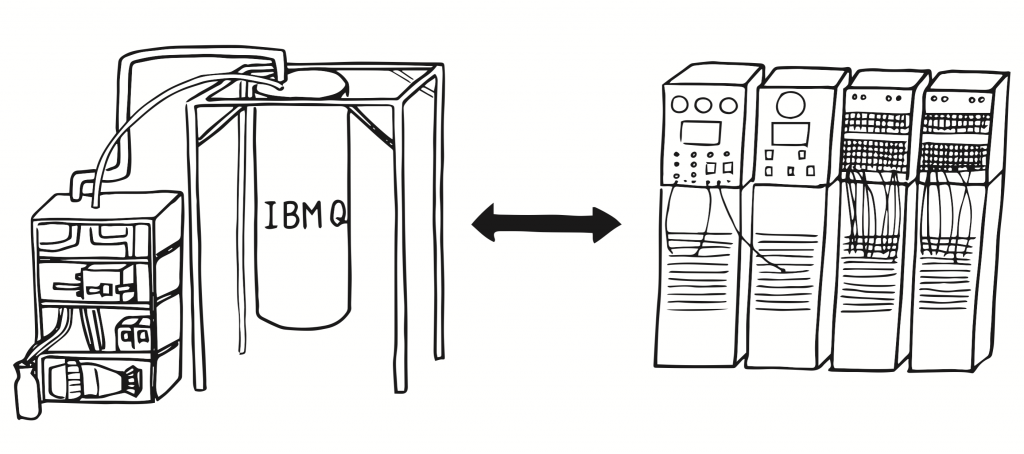

There are huge gaping holes in the tech stack that we will need to make quantum computing really useful, and the sooner we can fill them, the faster we will get to useful technology. But solving these problems isn’t necessarily ideally suited to academia. Large scale quantum processors will likely require the capabilities and process control of industrial fabs, and in the same way, a useful software stack will require professional development, so we’ll need industry one way or another. We need to work with engineers of various stripes, materials scientists and software engineers just to get the systems working, and we’ll need to work with domain experts to develop applications that actually satisfy a real demand.

My entire motivation for working on quantum computing is to see real technology emerge, so I’ve taken the leap into start-up land. At Horizon, we’re building up a team of people from both quantum and classical backgrounds to tackle some of the holes we see in the tech stack. Our focus is a bit different from the other companies out there, and as I can say more about what we are up to I will. For now, though, let me say that if you are working on realising QC hardware or software I would love to hear from you, learn about what you are up to and figure out if there is anything we can do to push the technology forward together. And if you’re someone looking to take the leap yourself, drop me a line and I’ll do my best to help.